Reflections on the Ring: A Note from Music Director James Conlon

Revised June 25, 2020

It is almost impossible to say anything about Richard Wagner that has not already been put to paper. The wealth of material about him exceeds that of all other artists, with the possible exception of William Shakespeare. He wrote more about his own art, philosophy and himself than any other composer. Nevertheless, I will attempt to articulate something about the significance of this Ring at LA Opera.

The 2010 production of Wagner’s full Der Ring des Nibelungen represented a major milestone in the still relatively short existence of LA Opera, as Los Angeles had never seen an indigenous production. Giving birth to this mammoth four-opera cycle is a major undertaking that challenges and defines an opera company. We set out to forge a heroic sword as Siegfried does, and carry it through a rite of passage and into a new era of maturity.

Producing the Ring expanded the capacity of the entire opera company. The demands on the orchestra and music staff, and on the stage personnel and company infrastructure, as well as the complex planning required for over two seasons all contributed to this expansion. The stretching of the listening capacities of our audience must be included in this list as well.

To veteran Wagner lovers, the Ring needs no introduction or advertisement. There are many who travel from city to city, country to country to see and discuss the latest production and compare notes. Their devotion demonstrates its enduring power to enchant.

The Ring occupies a central point in the history of Western art. It comprises music, drama, theater and poetry. It marries them on a scale unprecedented, unparalleled and unsurpassed. The power of this music, combined with the inexhaustible richness of myth, remains a necessity in our time.

Myths are open to limitless interpretations and every theatrical production is open to a vast number of possible realizations. Whatever the approach, the timelessness of the Ring’s messages is central to its strength, and integral to its essence. The Ring shares that power with myths and religious texts from around the world.

Updating to contemporary costuming or situating the Ring and its characters in familiar locales has been the dominating practice of the past several decades. There is no doubt that great creative work has resulted from exploring the theatricality of these options. That said, production values that were revolutionary and avant-garde a generation ago have now become, in many cases, clichés. The reductionism that underlies many productions weakens the full force of its mythical power. Rather than strengthen, it can dilute. Rather than provoking the imagination and its connection to our unconscious, it can constrain. Through specificity, our innate capacity to experience the work on multiple levels may be in danger of being reduced.

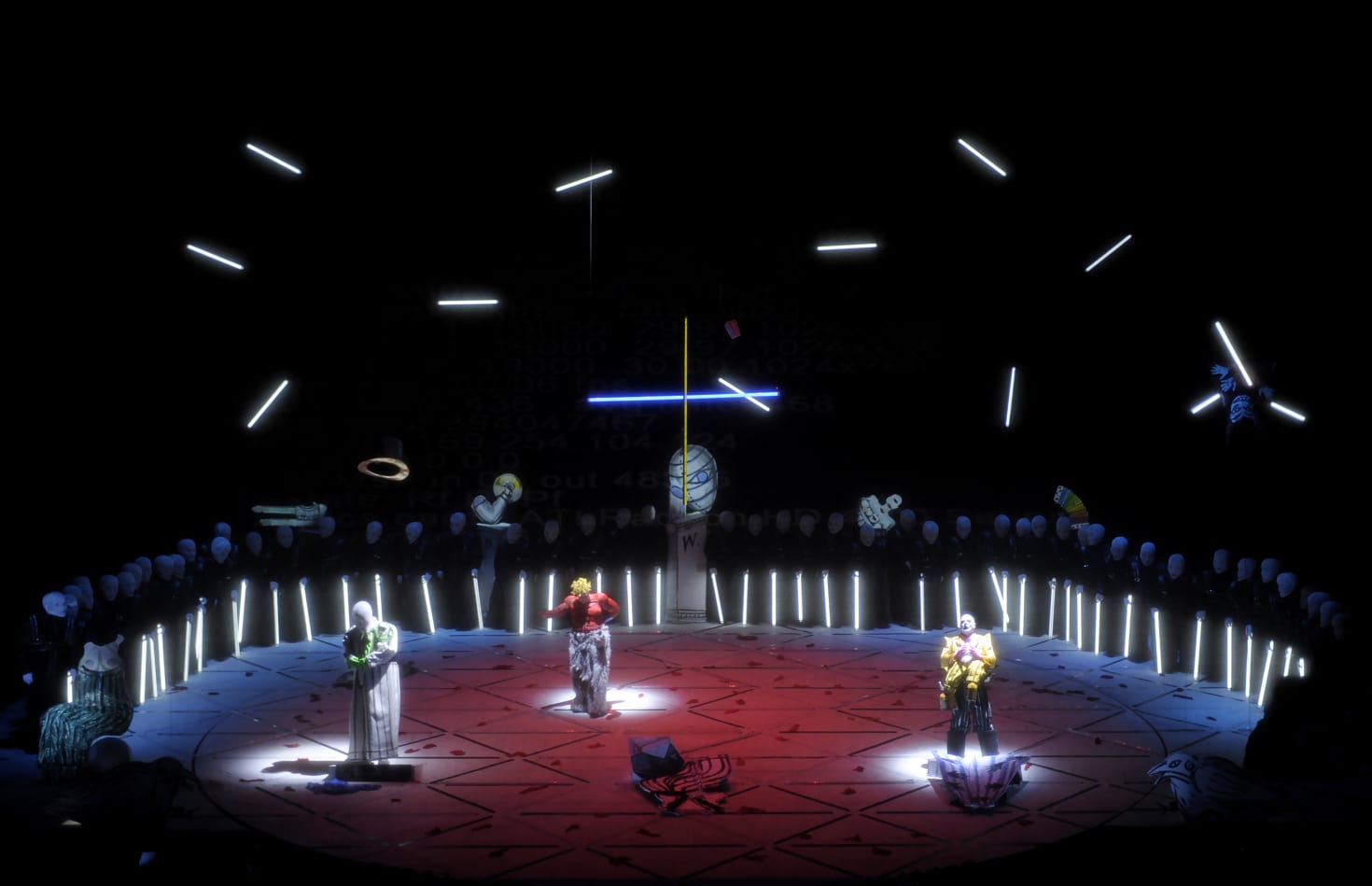

(Götterdämmerung, Act 3; photo: Monika Rittershaus)

On this occasion, the 2020 re-broadcasting of the LA Opera Ring on its tenth anniversary, these productions issues are not relevant. The unlimited emotional force of the music can be experienced in a special way. The ear is the direct medium to the heart and its emotions.

Whether “interpreted” as Freudian or Jungian, Marxist or Keynesian, as social criticism, political science or spiritual tract, the whole is greater than the interpretations, its fullness more powerful than its reduction. It is the conductor’s task to realize both the primordial power of the music and its drama. The two are intertwined and inseparable.

Neither director nor conductor should lose sight of the fact that the primary dramatist is the composer, and that the navigational chart to that drama is the music itself. Whereas the music can be said to have a “concert” life of its own outside the theater, the text of the Ring, recited without music, has less vitality. Any rendition of the dramatic or musical elements that does not take this into account risks foundering at its launch. The goal is to render this work in a way that it opens up that infinite space, as only it can.

The Operas

“The incomparable truth about myth is that it is true for all time, and its content, however closely compressed, is inexhaustible through the ages. The only task of the poet was to expound it.” Richard Wagner, Opera and Drama

“Mythology is an art form that points beyond history to what is timeless in human existence, helping us get beyond the chaotic flux of random events, and glimpse the core of reality.” Karen Armstrong, A Short History of Myth

What Richard Wagner writes about the poet is true for the composer; what Karen Armstrong writes about myth is true for music. Wagner sought, among so many other things, to create works that would unite the power of myth with the accomplishments of Shakespeare and Beethoven: idea, text and music.

The Ring cycle consists of a prelude and three consecutive “days.” To make a musical analogy, the Ring can be viewed as a four-part symphony, each movement self-contained and a complete within itself. Das Rheingold, the prelude, is the expository movement. Die Walküre is the slower, expressive lyric movement. Siegfried has been likened to a scherzo; the first act is witty, sharply bristling with demonic and Beethoven-like energy. Götterdämmerung is the sprawling free-form apocalyptic finale.

(John Treleaven in Siegfried, Act 3; photo: Monika Rittershaus)

In Die Walküre, the human dimension moves into the foreground and displaces the godly into the background. Mythology is not theology, and Wagner’s gods, like their Greek counterparts, behave more like humans more than disembodied spiritual beings. First seen on their mountaintop in Das Rheingold, Wotan and Fricka now “descend” to earth, where they operate according to human, domestic categories—as wife, husband and father. Sieglinde and Siegmund, the twin children of Wotan, and a mortal woman, are fully human protagonists.

Wotan’s humanity, for better and worse, becomes more apparent in this second movement. We see him ensnared by the consequences of self-contradiction. He has subverted his own law, and therefore his own power to rule. As he tries to find a way out of the trap that he has created for himself, we see anger, sadness and frustration and, most importantly, enormous love for his favorite daughter, Brünnhilde. His punishment will be to lose her and to lose his other most precious possession, power. This is one of the most tragic (and tragically beautiful) ironies in the Ring—that Wotan, who thinks he must punish Brünnhilde in order to preserve the integrity of his divine law, punishes himself above all. It would be hard to imagine a musical rendering of paternal love greater than Wotan’s farewell to his most beloved daughter. In its exquisite monumentality, the end of Act Three is a counterweight to the erotic love that triumphs at the end of Act One.

From the beginning, Siegmund and Sieglinde win our empathy. We see them meet, fall in love and discover their mutual parentage. This is not a sweet infatuation, but the mutual recognition of an apparently pre-existing bond. They experience a liberating and exultant revelation of wholeness, the re-union of souls. They are the two complementary beings separated in a distant past according to the ancient Greek notion of the hermaphroditic division described in Plato’s Symposium. Their existence has been informed by their yearning for the missing half. By the time they recognize that they are indeed twins, their erotic union is already at hand. This knowledge does not deter them from consummating that love, nor us, from understanding and even sympathizing.

Wagner has accomplished the seemingly impossible. He has presented incestuous love on the stage and has not only gotten away with it, he has thoroughly engaged our empathy for the couple through the sheer emotional power of his music. He recognized what Freud was to identify decades later, the titanic power of breaking sexual taboos. And Wagner was proud to do so: “Thus, sexual love is the revolutionary, who breaks down the narrow confines of the family, to widen it itself into the broader reach of human society.” He observed that by breaking out of society’s constraints, we discover the full power of our creativity; the stronger the constraint, the mightier the force. Here, by portraying the breaking of the one virtually universal taboo, he raises the ante on the intoxicating power of “forbidden love.” Only in the second act of Tristan und Isolde, a decade later, will the erotic perfection of this first act of Die Walküre be equaled.

It is striking to note that, in Die Walküre, with the exception of Fricka and Hunding, every character is a child of Wotan. He has fathered each of the Valkyries with Erda, and Siegmund and Sieglinde with an unnamed mortal woman. Fricka, goddess of marriage, home and hearth, with a mixture of godlike righteous indignation and justified jealousy, condemns the young couple. Wotan had previously subverted his own laws in his dealings with the giants, but Fricka insists that her laws be observed to the letter. All too human, she insists on vengeance, and, by extension, repays Wotan for his infidelities. Fricka’s jealousy extends far beyond domestic marital woes, however. Her call for Siegmund’s punishment is both personal and political: her husband’s disloyalty (both to his marriage and his own laws) diminishes her power and status. While Wotan’s defense of Siegmund’s and Sieglinde’s unconditional love is valid and important, Fricka argues as an act of self-preservation. In the context of a clear power disparity, Siegmund’s punishment is politically necessary for her. She will have no authority as a goddess if Wotan encourages the open defiance of her laws. Buckling under Fricka’s demands, Wotan unwillingly abandons his son to his fate.

(The Ride of the Valkyries, Die Walküre, Act 3; photo: Monika Rittershaus)

Her instrument in this punishment is Hunding, the other “wronged” spouse. Barely human, he is brutal, cruel and cold. Having taken Sieglinde by force to be his wife, he has treated her with contempt and condemned her to a life of servitude. But Fricka is not concerned with the content of particular (in)human unions, but in the universal application of her laws. Having won her victory, she walks off the stage of the Ring, never to be seen again. Her continued existence is implied in Götterdämmerung—where she sits with the gods in Walhalla, all bound by astonishment and trepidation, awaiting their certain doom. It is as if Fricka, along with the rest of Wotan’s retinue, has already resigned herself, occupying the place assigned to mythical gods in modernity—depicted in art but nevermore to be seen, referred to but nevermore to be heard.

As Fricka exits, a new species of love, a love that is not proscriptive and lawful, but free and, therefore, enduring, enters the drama. Brünnhilde, the favorite daughter of Wotan, will take center stage as the force of this new, free love, never to relinquish it. Freia’s gentle beauty recedes. Sieglinde’s passionate and winning humanity will end in her young death. Brünnhilde will set out on her path from youthful warrior to her eventual role as the embodiment of world-encompassing, redemptive love. By disobeying Wotan’s orders, she defines her new adulthood and demonstrates empathetic and intuitive love by executing his will in defiance of his words. In a rite of passage, she, in Freudian terms, destroys the fatherly role of Wotan, just as Siegfried will accomplish the ultimate destruction of Wotan’s godly status, when he unknowingly meets his grandfather (as Oedipus met King Laius) and breaks his spear. But in Brünnhilde’s defiance of Wotan’s commands, she shows that, in contrast to Fricka, she understands the spirit of love to be superior to the law as did, in her fateful way, Sieglinde.

As in Greek tragedy, the gods punish any infraction against their authority. Forbidden love must be chastised. King Oedipus pays for his unwitting incestuous love. How much more must Siegmund and Sieglinde, twins, pay for their incestuous love, consummated with full knowledge of their common parentage? Sieglinde and Brünnhilde, biologically half-sisters, are perfect spiritual siblings; conceived to accomplish their father’s will, they choose to live according to their understanding of the demands of love, accepting total responsibility for the price of their autonomy and each embracing their respective punishments.

Is Siegfried the metaphorical scherzo of a four-movement symphony? Most analogies of this sort break down under the microscope, but still, there is some justification for the comparison. Though it is by no measure a comedy, Siegfried contains more banter, repartee and light moments than any other opera in the Ring. Here is an homage to Beethoven, who transformed the minuet into the scherzo (which means “joke” in Italian). The scenes between Siegfried and Mime are infused with almost manic energy, reminiscent of the nine symphonies of Wagner’s mighty predecessor. Could one say that Siegfried is a heroic scherzo or, conversely, a scherzo about a hero?

Moreover, the third opera of the Ring also draws more heavily from fairytale tropes than the other three. The list of elements common to that genre is long: a dark forest, a gnome, a sword with astounding strength, a witch’s broth, a dragon (slain by the hero), serpent’s blood (which empowers the hero to read thoughts and understand a forest bird’s twittering), an enchanting and enchanted encounter with nature, a magic fire, and, finally, a sleeping beauty to be awakened with a kiss.

Siegfried is a peculiar type of hero if he even be called one at all. True, like Hercules, he performs acts of great bravery and physical strength. He, like Parsifal (the “reiner Tor,” pure fool), is not impressive on an emotional or intellectual level. He defends neither kin nor country, ideology nor an enlightened vision. To what does he dedicate his great strengths? We discover him as an adolescent, predictably self-involved and narcissistic. But, in the end, the heroics are revealed in his kinship with his “father” the creator (with a small c)—Wagner himself. The composer, wielding the mighty sword he has forged for himself out of broken pieces of Western civilization (his view), will revolutionize music and, with it, the world.

(Vitalij Kowaljow (Wotan), Gordon Hawkins (Alberich) and Arnold Bezuyen (Loge) in Das Rheingold; photo: Monika Rittershaus)

Siegfried knows no fear. In mythology and scriptures, the status of hero is usually conferred on those who experience fear and/or doubt as they confront a defining struggle, which they ultimately win. There is no garden on the Mount of Olives for Siegfried. His “heroic acts” are based on his brawn, not his brains. He forges a sword, kills a dragon and walks through fire. His less than exalted goals are few. The first is to annoy and ultimately murder Mime, the Nibelung dwarf who describes himself as both Siegfried’s father and mother. His second is to learn the meaning of fear. Though not ignoble, it is hardly a heroic quest. After being prompted by the Woodbird, he decides he can learn fear by walking through a fire to find a beautiful woman. In a Freudian manner, his rite of passage is to wield his sword to kill Mime, his surrogate father, then break the spear, a symbol of power and law, of his grandfather, Wotan. Like Oedipus, who unknowingly murders his father (the king) at a crossroads, then unwittingly marries his mother, Jocasta; Siegfried, equally ignorant, symbolically does the same, continues on his journey and will “marry” his aunt, Brünnhilde.

Wagner, as he did in Die Walküre, has again fused two stories into one work. The saga of Wotan, Erda and the curse of the ring intersect with that of Siegfried, whose trajectory from adolescence to manhood has its own dynamics. As he knows next to nothing about human society (which will become woefully apparent in Götterdämmerung), his role in that cosmic drama is accidental and unconscious, almost preordained. The world of Die Walküre, which was more human than that of Das Rheingold by half, recounts the struggle of the deities Wotan, Fricka, and the half-deity Brünnhilde, juxtaposed with the human story of a brother and sister united in a forbidden love. They perish at the hands of a brutal husband, Hunding, in alliance with a righteously indignant deity wife, Fricka. The issue of that loving, forbidden incestuous union, young Siegfried’s fairytale-like story is grafted onto the remaining threads of the two previous operas. It opens a new world to Siegfried and the reborn and fully human Brünnhilde, defrocked of her divinity. It portends the closing of the world of Wotan, Erda and the gods, Fafner and the race of giants. Only Alberich, the ring and its curse, continue onwards.

So, once again, Siegfried is one music drama with two stories. The fairy tale ends with the young couple’s exultant discovery of love. They will live happily ever after.

Except of course, they won’t. Just as with the glorious celebration of the gods’ entrance into Walhalla at the end of Das Rheingold, the apparent “triumph” at the end of Siegfried is illusory. Siegfried’s story goes on, the fairytale aspect recedes, the young couple descend the mountain, and Siegfried enters human society. The enlightened Brünnhilde will leave her naïve Siegfried to his own devices and, before long, he is ensnared both by a fractured human society and the unresolved remnants of Wotan’s legacy.

In fact, the cosmic myth dominates. Siegfried has been the plaything of the gods after all. Together with Brünnhilde, will he show humanity the way out of the Age of the Gods and into the New Age of the heroic? Will intrepid feats of human strength and compassionate love will mend the world. Promises of valiant deeds will transform humanity. Will Götterdämmerung ultimately show this all to be illusory? Can the heroes atone for the sins of the father through self-sacrifice and courageous deeds? Can the world be renewed through compassionate love? Not yet. Only after the universe has regained its balance with the restitution of the gold to its rightful place in nature and, by extension, the individual lust for power and drive for world domination is eradicated or at least neutralized.

Siegfried is by far the most exuberant and optimistic of the Ring operas. It pulses with pure excitement and moments of distilled youthful vigor. Each act climaxes in exultant primal energy: in Act I, Siegfried’s forging of the sword reinvents the wheel, achieving through work (“schaffen”) an almost orgasmic excitement similar to his parents’ erotic union; in Act II, he dashes off with an unquestioning naivete and cheerfulness to treat every adventure as his toy; in Act III, he awakens the sleeping beauty and, through her, discovers fear, woman and the beginning of adulthood in joyous, triumphant partnership with the orchestra.

(Richard Paul Fink (Alberich) and Eric Halfvarson (Hagen) in Götterdämmerung; photo: Monika Rittershaus)

Siegfried is the Ring’s second depiction of Wotan’s progeny discovering love. The opera finishes with roaring ecstasy. The newly found couple exclaims: “She/He is forever and always for me, inheritance and possession, one and all, shining love, laughing death” (“lachender Tod”). They are granted the fulfillment and consummation of their new love, which will be denied to Tristan and Isolde. In contrast to Sieglinde and Siegmund (who experience the reunion of a single soul, sharing memories of a distantly arcane bond), the young heroic couple share a mutual sexual awakening. Wotan’s grandiose plans, now dead and gone forever, open the path to create the new human reality: not a world of gods, but of humans. Wotan’s daughter and grandson mate, in the Ring’s second depiction of incestuous love; the Wälsung race should continue after all. Fricka is long gone, and this time cannot contrive to punish them. The New Age has dawned; the Sleeping Beauty has awoken; Turandot’s heart has melted; the heroes will save the earth. We identify with their joy, and our own unrealized heroic fantasies. The exultation that we feel with them seems resplendently justified. If we did not know what happens in Götterdämmerung, we would believe that the ring’s curse had been defied, true love had triumphed and that they, and we, would live happily ever after.

“Away then with lordly splendor, godly pomp’s arrogant shame! Let all that I have built disintegrate! I renounce my work; only one thing do I desire still: the end… the end…”

Wotan, with a bitter mixture of resignation, desire and dread, utters these terrifying words to Brünnhilde in the second act of Die Walküre. And thus it is for us all, or so it seems.

The end of time, and of the world as we know it, continues to preoccupy human beings as it probably has from the dawn of consciousness. Apocalyptic visions, beliefs and fantasies are a staple throughout human history. Artists, musicians and writers have grappled with and drawn inspiration from eschatological mythologies. Both as music and theater, Götterdämmerung stands as the most massive achievement in apocalyptic art.

The powerful voice of the orchestra as protagonist, including extended symphonic passages, is liberated beyond any previous operatic example in the employment of absolute music. It unleashes drama in a torrent of expression, revealing the inarticulate subliminal unconscious and the cosmic forces.

The jubilation at the end of Siegfried has heralded a new age and a new heroic couple. They will descend from the mountain, like Moses, Jesus and Mohammed, prepared to reveal a new moral order. The distant, otherworldly mountain repeatedly served Wagner. The eroticism of Venusberg, the spirituality of Montsalvat (home of the Holy Grail), Walhalla (temple of illusory transient power), Brünnhilde’s rock (scene of the confinement and “rebirth” of a new prophetess)—a mountainous sojourn signifies a source of transformative revelation (the “apocalypse” of the Greeks). But Siegfried is not a prophet and not really even a hero. No time will be lost before he falls into the trap of human intrigue. Brünnhilde, however, through her innate understanding of enlightened sympathy and compassion, will heroically serve as catalyst to this cosmic drama’s denouement.

(Vitalij Kowaljow (Wotan) and Linda Watson (Brünnhilde) in Die Walküre, Act 3; photo: Monika Rittershaus)

“Kurz vor Mitternacht” (“Shortly Before Midnight”) could be the subtitle of this final chapter of the four-work music drama. The sense that the end of time is at hand imbues the work from its ominous, first chords. A magnetic pull draws the listener toward that end, inspiring dread and desire in equal measure—terror of the unknown and desire for the relief from the feeling of trepidation.

The cosmic myth of Wotan, the gods and Valhalla collide with the heroic drama of Siegfried’s Death (Wagner’s original title for this work), and together they and their worlds are destroyed.

But is the end of time also the beginning of time? There is already a hint of ambiguity in the title. In German, "Dämmerung" (dim light) refers to both dawn and dusk. The traditional English translation, Twilight of the Gods, is clearly the meaning Wagner employs. Apocalypse, in its etymological sense of revelation or disclosure, implies continuation of the cosmos after its true nature has been uncovered. The dim light of dusk should first re-emerge in the dim light of dawn, after the darkness of night.

The old-world order, that of the gods, is finished. Is this the end of the world or will it now be replaced by a new (better?) order? Or neither? Has the harmony of the universe been restored with the return of the gold to the Rhine? If so, has its restoration brought history to a close, a point of stasis or another beginning? Is cosmic history linear or cyclical? Has Brünnhilde’s transformation—from daughter of the gods to fully human—ushered in a new era? Will the new world order of evolved humanity build society without gods (or even heroes), based on compassion, justice and freedom? Will Brünnhilde’s example serve as a model?

Or will new gods arise and break their own contracts and laws? Will Alberich steal the gold again and challenge the new gods in their mutual lust for power? Will mankind have learned from a purifying baptism of fire and water, or repeat this drama cyclically?

At the end, presumably all of the protagonists have died, either burnt by fire or drowned by water. Only the Rhinemaidens survive, probably to return to their preordained function of guarding the Rhinegold. Is it significant that, besides them, only Alberich remains, for whom there is no accounting? Are he and the Rhinemaidens destined for another confrontation? Will the “fall of Man” repeat itself?

There are no answers, only questions. The sense of dread of the impending end of time gives way to cathartic completion. The world has been purged, literally ignited by Brünnhilde and bathed in the overflowing waters of the Rhine. And she, evolved and revolutionary (possibly embodying Wagner’s own philosophical trajectory), brings the end: upon herself and the order into which she was born, and upon the world in which she has grown to maturity. She has a power, through redemptive love, to transform the world. It is a power never attained by Alberich (who renounced love), a power lost by Wotan (who contradicted his own laws).

The immolation scene recalls Isolde’s Liebestod (love-death). The music transcends the word. Brünnhilde’s death, a journey into an envisioned eternity of her own creation, a place where she can love without interruption—a luxury denied her both in Valhalla and on earth—is simultaneously the annihilation of the world order. There seems to be universality to “end-of-time” scenarios that run throughout most cultures. Apocalyptic dread merges the individual and the cosmic? And so it is with Brünnhilde’s death and the end of the world order. Are we destined for new life, cyclical repetition or extinction?

Wagner believes that redemptive love is the powerful force that converts and emancipates humanity. Brünnhilde, nurtured by filial devotion, and autonomous mature love, embodies that power. She is the agent of the restoration of Nature’s harmony, which regains its balance with the restitution of the gold. Alberich’s renunciation of love is itself renounced, and the lust for power is vanquished by the mandates of compassionate love. This poetic, four-movement, symphonic music drama, this colossus of Western civilization, ends not with the false idolatry of Wotan’s godly pomp, but with Wagner’s vision of spiritual transformation. An epic myth, conceived in a spirit of revolutionary activism, has, in the course of time, transformed itself. Through Wagner’s years of reflection, resignation and philosophical metamorphosis, that myth, culminates in a message of cosmic redemption.

© 2020 James Conlon